The Kigluaik Mountains north of Nome are more than landscape: they are sacred sites where Kauweragmuit people have journeyed for prophecy and survival, gathered for ceremony, and maintained connections spanning generations. Now, they face a threat from the proposed Graphite Creek mine, a large-scale open-pit graphite mine that would be located in the Kigluaik Mountains, approximately 40 miles north of Nome.

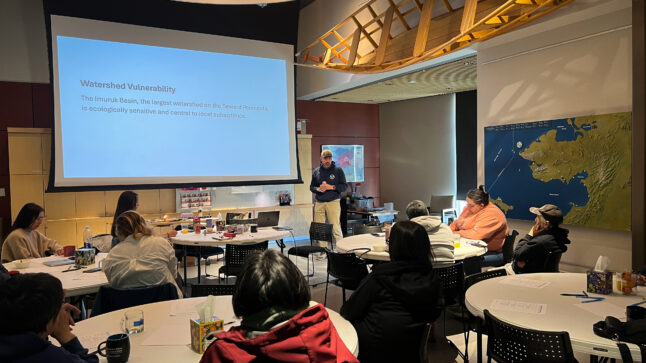

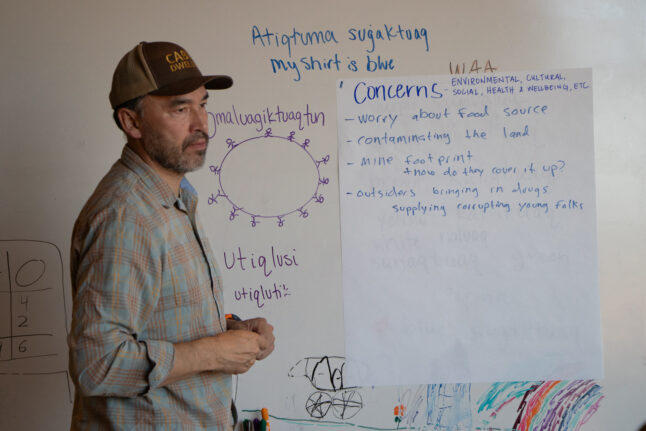

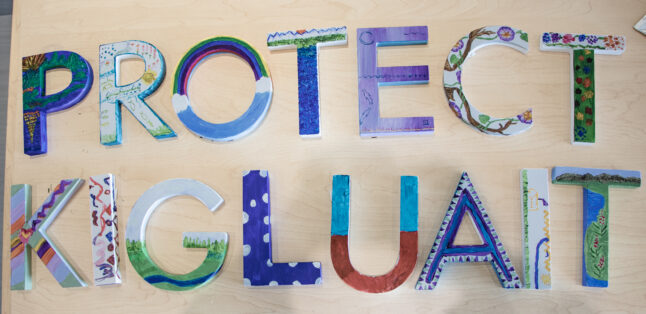

Last month, Adelaine (Addy) Ahmasuk brought this issue into sharp focus. Through Sacred Kigluait, a community-based organization focused on educating community members about hardrock mining impacts and revitalizing ancestral connections to the Kigluaik as a sacred site, Addy convened 23 tribal leaders, knowledge holders, and concerned community members with support from a grant from Alaska Conservation Foundation (ACF). Over two days, participants from Nome, Teller, Brevig Mission, Mary’s Igloo, Elim, and Anchorage united around a common cause: ensuring their voice and concerns related to the Graphite Creek project backed by Canadian company Graphite One were heard.

This gathering exemplifies exactly why ACF created the Alaska Mining Impacts Network (AKMIN). As an engaged AKMIN member and ACF grant recipient, Addy’s work demonstrates how local leaders, equipped with resources and connections, can mobilize their communities to protect what matters most.

What the Graphite Creek Project Threatens

If this mine is permitted, it could cause irreversible damage to the region’s homelands, culture, and health. The proposed mine would inhibit hunters, gatherers, fishers, hikers, culture bearers, and the public from accessing the mine site and surrounding areas.

Participants from the Villages of Teller, Mary’s Igloo, and Brevig Mission spoke about how the mine would disrupt harvesting and teaching at Windy Cove, a place where families gather to pick berries, collect greens, fish, and pass on knowledge. One participant said, “Most of the food we eat is what we hunt and gather. We fill many freezers every year with Native foods that we eat and share.”

The open pit mine would permanently scar the mountains, generate toxic waste that could require centuries of cleanup, permanently eliminate over 380 acres of waters and wetlands (an area larger than 290 football fields), and release large amounts of diesel emissions. It could also threaten water quality in communities that still rely on springs for drinking water. The US Department of Defense has already invested tens of millions of dollars in Graphite One without legally required tribal consultation.

Decades of Knowledge

A participant shared a technical review of Graphite One’s feasibility study that highlighted major gaps. The study focuses on financial outcomes but does not show whether water treatment and tailings systems can withstand extreme weather or prevent toxic spills. Elders shared the cultural geography of the area: springs, sacred places, and generational practices tied to the land. They shared the cultural geography of the Kigluaik Mountains: sacred sites, springs, and ancestral practices. These perspectives reveal what no feasibility study can measure: the mine would disrupt an interconnected way of life dependent on healthy land, water, and community.

Austin told participants, “You carry decades of knowledge and that knowledge belongs in the permitting process.” Participants reiterated that a single disturbance to water quality would immediately endanger both human consumption and the fish and animals people rely on for food.

Imagining a Different Future

A participant from Teller, posed the central question: “This mine is just one generation, what about these other revenues that are multigenerational?” The gathering wasn’t just about raising concerns with a potential mine; it was about imagining a future where the Kigluaik Mountains support sustainable livelihoods, cultural practices continue, and communities can pass down knowledge and resources to future generations.

Participants discussed sustainable, community-led alternatives that prioritize long-term well-being over short-term extraction, such as revitalizing reindeer husbandry, developing Indigenous-led ecotourism in the pristine Kigluaik Mountains, building game processing facilities and Native food restaurants, establishing guardian programs to compensate local stewards of the land, and supporting traditional arts markets and cultural preservation initiatives.

These solutions are rooted in sustaining what already exists. “We have a subsistence economy with a cash overlay,” one participant said, a reminder that hunting, fishing, gathering, and bartering are not just cultural tradition but an active, functioning economic system.

What’s Next?

The US Army Corps of Engineers has opened a public comment period on a permit Graphite One needs to move forward. This permit would allow the company to dig up and fill wetlands, streams, and other waters and to build an industrial road through Mosquito Pass. In its notice, the agency states that the mine plan would permanently remove hundreds of acres of wetlands and divert streams. Tribes have the right to be consulted, and the public has the right to comment before any permit is granted.

Public comments on the Graphite Creek permit are due Nov 30, 2025. Sacred Kigluait is calling on anyone who cares about sacred lands, clean water, subsistence, and Indigenous rights to submit comments.

With many residents unaware of the ongoing permit process, Sacred Kigluait partnered with Alaska Community Action on Toxics to build an online tool that provides background information and enables people to submit a comment directly to the agency.

How the Alaska Mining Impacts Network Makes This Work Possible

As a funder, Alaska Conservation Foundation’s role is to provide resources when frontline leaders like Addy need them most. Our grantmaking programs offer flexible funding so grassroots organizations can respond to urgent threats on their own terms, with their own strategies.

Through the Alaska Mining Impacts Network (AKMIN), we help connect these leaders across Alaska so they can share knowledge, strategies, and solidarity with each other. The expertise, the vision, and the power comes from communities themselves. AKMIN creates space for that connection, and can provide funding through the Alaska Mining Impacts & Prevention fund. Community-led conservation means frontline leaders define the path forward, organize on their own terms, and protect what matters most.