Photography By Schuyler Alig

From mapping coastal erosion to preserving vital ecosystems, Geographic Information System (GIS) technology is giving Alaskan communities the power to protect their lands and ways of life. Indigenous communities have been too often excluded from land resource management decisions despite being the stewards since time immemorial.

The Bristol Bay Region, known for its rich wild salmon populations, is one of the most biodiverse regions in the world, providing habitat for 29 fish species, more than 190 bird species, and over 40 terrestrial mammals (EPA, About Bristol Bay). The Yup’ik, Dena’ina, and Sugpiaq peoples of Southwest Alaska have lived within the Bristol Bay region for millennia, primarily subsisting on sayak – the sockeye salmon. Although this region supports more wild salmon populations than anywhere else on Earth to this day, impacts from climate change are evident.

Last month, Bristol Bay residents gathered in Dillingham for a week-long course to build technical proficiencies in resource mapping to promote community-led planning. This class was a partnership with Bristol Bay Native Corporation, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, University of Alaska Fairbanks, and St. Mary’s University. It explored geospatial concepts that can be applied globally by focusing on issues directly related to climate changes in rural Alaskan communities. Northern Latitudes Partnership (NLP) helped coordinate logistics and outreach for the capacity-building portion of the project. Course funding was provided by National Fish and Wildlife Service for course costs as well as student travel, room and board. NLP, housed at the Alaska Conservation Foundation (ACF) is often invited to play the role of a convener bringing together a diverse group of stakeholders. These unique networks made up of agencies, Tribes, Canadian First Nations, communities, nonprofits and academics span Alaska and northwest Canada. Focusing on collaborative conservation, for addressing the rapidly changing climate and development pressures in the north.

In rural Alaskan communities, only accessible by boat or plane, resources and personnel can be limited. Geospatial tools like ArcGIS Pro and ArcGIS can help communities record, track, analyze environmental data, and make informed decisions around climate adaptation. Spatial literacy and data records enable long-term planning; strengthening community resilience.

In rural Alaskan communities, only accessible by boat or plane, resources and personnel can be limited. Geospatial tools like ArcGIS Pro and ArcGIS can help communities record, track, analyze environmental data, and make informed decisions around climate adaptation. Spatial literacy and data records enable long-term planning; strengthening community resilience.

One student, Larissa Kramer works on Bristol Bay Native Corporation’s (BBNC) wetland mapping initiative, recording wetland environments and coast lines while tracking changes. This mapping initiative focuses on improving regional habitat management and supporting conservation planning in the Bristol Bay area. The goal, is to develop a local workforce skilled in GIS empowering communities to lead conservation efforts. GIS is also commonly used for land and resource management, including organizing native land allotments, drawing hunting boundaries, or general jurisdiction data.

NLP takes a community-first approach, bringing together Indigenous knowledge and applied science to inform government agencies and other decision makers. Indigenous knowledge was not always valued or heard as it did not always fit the scientific vernacular. New potential for transformation comes when combining Indigenous knowledge of the land with modern tools like geospatial mapping and data science. When data is presented on a map, we suddenly have locational context for the information giving it more meaning. But who is making the maps dictating the locational context? No one truly knows the geography, history and patterns of the land as well as those who have been there for generations. Native communities have the greatest context to give for geospatial initiatives. Through collaboration, NLP strengthens relationships between tribes and all levels of government, ensuring Indigenous voices are central in the decision-making process.

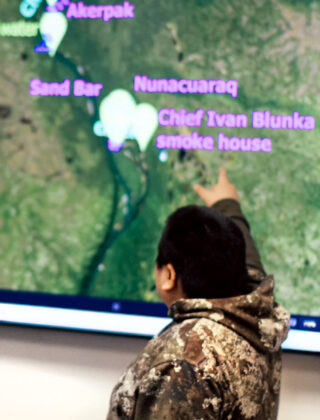

Cavelia Wonhola created a map of the Mulchatna River near New Stuyahok where he grew up and fished. He used symbols and a key to show everything from the old and new channels the river has carved to the Indigenous Place Names. This map is not just a collection of coordinates but tells a story of time and its effects on an environment and community. GIS technology bridges the gap between indigenous communities and science. Additionally, GIS initiatives bring communities sustainable capacity building and workforce development. Increasing opportunities in science and technology helps retain young people in their communities with the opportunity to work with the land and having a means to survive. This also provides opportunity beyond the fishing industry that is becoming more volatile with the effects of climate change.

Deenaalee Hodgdon (Co-Founder of The Smokehouse Collective) collected 14 data points around the Smokehouse Collective to build a map on ArcGIS for her field application. The Smokehouse Collective is an Indigenous food hub that focuses on restoring access to salmon from Bristol Bay for climate-impacted communities across Alaska. By partnering with local airlines, volunteers, and utilizing portable deep freezer technology, the Collective aims to establish a network for harvesting, processing, and distributing salmon. This initiative not only addresses food security, but revitalizes traditional trade practices, allowing communities to reconnect with their cultural heritage. As part of its mission, the Collective offers a space for community members who have lost access to salmon to travel to Bristol Bay and participate in the cultural processing methods that have sustained them for generations.

Deenaalee mapped out existing survey markers and information structure of the collective land to better plan as they begin building structures. She plans to work with community members taking into account where the wells are, where is the best light for gardens and where there will be room to eventually expand. This is just the beginning of a community led project working to preserve traditions of the land and waters for generations to come.

By offering GIS education and hands-on experience, initiatives like the Community GIS course in Dillingham help empower locals and future leaders with the tools needed to monitor environmental changes, predict future impacts, and develop actionable climate adaptation plans. Ultimately, this approach bridges the gap between Indigenous knowledge and scientific methodologies, fostering stronger, more resilient communities in the face of climate change and an ever evolving north. Through collaboration, NLP strengthens relationships between tribes and government, ensuring Indigenous voices are central in the decision-making process of land management.